Rachel Martin

“Noble Work”:

Recognizing Those We Need To Keep America Running

September 19 to November 6, 2019

There is value in good work. Whether by a banker or bricklayer, work done well contributes to the flourishing of communities. But in a society that places great value on image and status, the contributions of the American working class are sometimes overlooked.

A poster of a smiling bank manager may adorn the entrance of a bank, but what thought do we give to the workers who built the walls? The architect may have their name engraved on a building, but what about the workers who carried out their plan? These workers support the physical needs of neighborhoods, organizations, and individuals. They are the hands and feet of society. Without them, the world would grind to a halt.

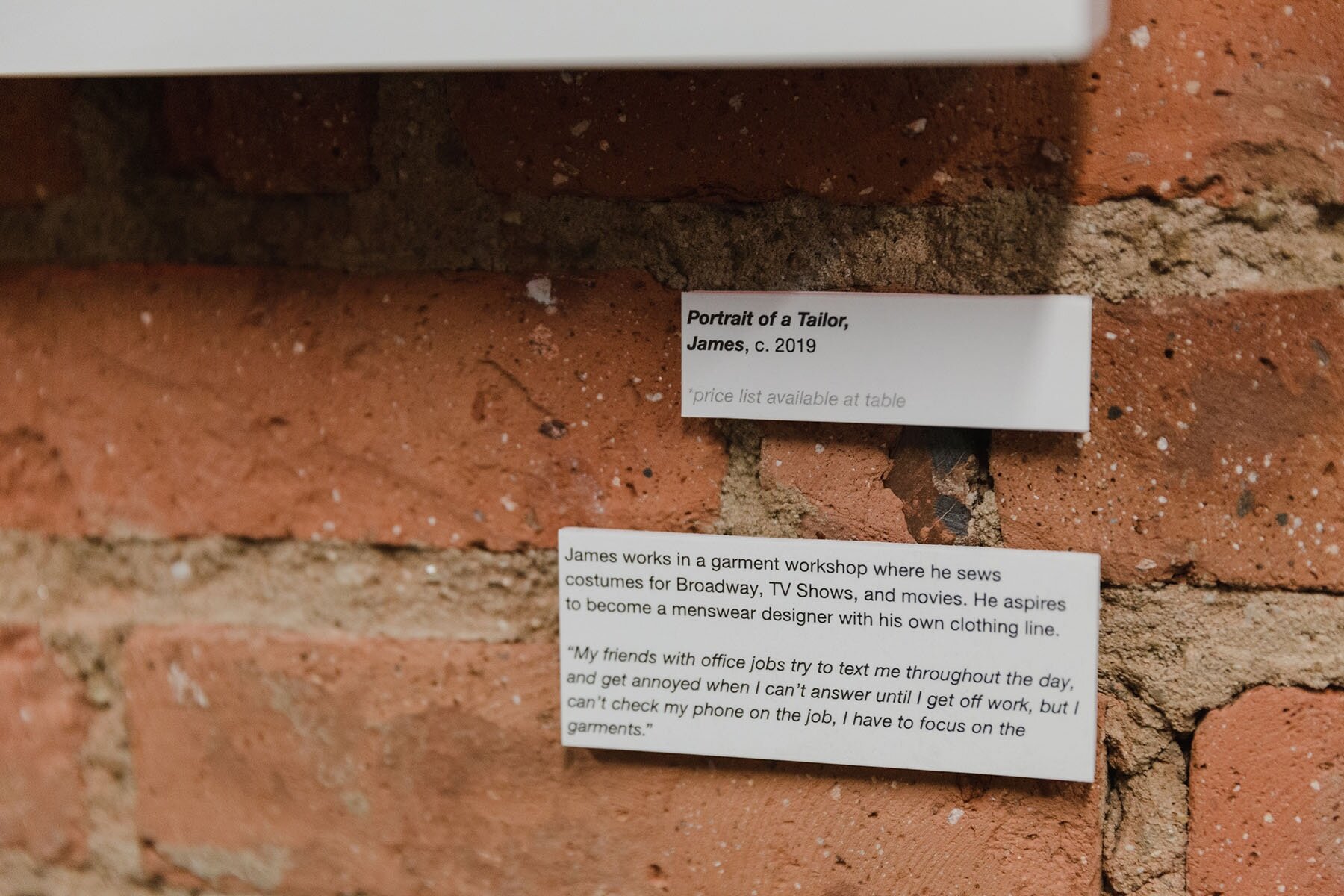

Rachel Martin’s portraits of the American working class help us see the value and dignity that are found in all as they work as an act of love and support for their families, build and care for their communities, pursue their goals, and take pride in a job well done.

Opening |Wednesday, September 19 | 6:30-8:30 pm

Gallery Talk | Thursday, October 24 | 7:00-8:30 pm | Free tickets here

“Noble Work” | Photographs

Interview with Rachel Martin

What did you learn while creating these portraits that surprised you?

People surprised me. I have had some really amazing and eye-opening experiences during this process. I have enjoyed getting to know some of my subjects, hearing a bit of their story and some of their hopes and dreams for the future. For some of them, this is just a season in their lives. They are working hard to make it in America, doing all they can to “move up” in the world. They see their work as a means to an end. Others are in love with what they do. They see the value and importance of their role and feel blessed that they get the opportunity to wake up and do their job. I have come to see that both are admirable. I have also grown extremely thankful for the work that my subjects do. Without them the sidewalk outside my apartment would still be broken, the trash at the beach would be overflowing and the gallery itself would be falling apart.

I also learned that the tour busses by Port Authority drop their prices by 50% right before the bus is about to leave, carpenters are now more likely to use metal than wood, and some firefighters still have Dalmatians.

What's your personal connection to blue-collar workers? What drew you personally to this project?

I grew up living a dual life, caught between classes. My summers were spent hanging around in a welding shop in my 3,000 person hometown in rural south Texas. I spent my time answering phones in the sweltering office and watching Bonanza. During the school year, I would hang out with my private school friends in the mini-mansions of suburbia, surrounded by the children of surgeons and NBA players. I was able to see these two sides of America and make deep connections with people in both worlds. What drew me into this subject matter was my personal experience witnessing this class divide in America, and the desire to bring disparate people groups together.

How has doing this project changed the way you think?

This project has definitely changed the way I view New York City. I spend most of my days working out of an office in midtown. I would get to work and complain about the terrible commute or the broken sidewalks without actually thinking about all that goes into making a city run. One of my favorite experiences was photographing the men that were fixing the sidewalk outside my apartment. They were so kind to take a break from their work to let me take their portrait. Now every day when I step out of my apartment, instead of complaining about everything that needs to be fixed, I start the day being thankful for Balwinder and his crew of sidewalk repairmen.

How does this project fit into the rest of your life as an artist: what you've made before, and what you're working on now?

I did not realize until much later in life that my unique childhood, caught between two very different environments, has enabled me to be both highly adaptable and a natural connector: a bridge between seemingly opposed worlds. That is true of my photographic subject matter as well. I am drawn to photo projects that aim to draw people together.

The other photographic series that I am currently working on is around the topic of the American church and race. To me, one of the most important things that photography or media at large can do is enable the viewer to see the world from another's eyes. I hope that my work will play some small part in softening hearts and minds to the lives of people they may not know or understand, especially in this time of such strife and division in our country.

What do you hope people will experience when they come to your show?

I would like the viewer to see those pictured as individuals with inherent value and merit, and as people whose work is vitally important to our society at large. I photographed my subjects on a large-format view camera that was built around 1950. The process of taking each image is time-consuming and expensive. The camera is also not something you typically see, so it causes the subject to be more stately and composed when posing for the photo. I intentionally photographed my subjects in this way to connect the reality of their everyday work environment to the formality and grandeur of 18th-century paintings and through the process, honor the subject and their work.

Curated by Eva Ting